Harmonisation. All patients provided written informed consent to

participate according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are reported as frequencies

and percentages. OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product-

limit methods

[10] ;median OS and 95% CI were reported using

Brookmeyer and Crowley methods

[11]; 95% CIs were constructed via

log-log transformation. Hazard ratios for nivolumab versus everolimus

were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model with

treatment group as a single covariate

[12] .Unstratified hazard ratios

and corresponding 95% CIs were used to generate a forest plot of OS

comprising each subgroup. A forest plot of the unweighted differences in

ORR between nivolumab and everolimus and corresponding 95% CI using

the Newcombe approach was produced across subgroups

[13]. To assess

whether the relationship between OS and treatment differed by various

patient characteristics of interest, we separately tested the interaction

between treatment and each baseline characteristic using a Cox

proportional hazards model. Similarly, for ORR and treatment-related

adverse event (TRAE) rates, the interaction between treatment and each

baseline characteristic was tested using a logistic regression model.

Continuous variables were only used for the interaction test for age (in

years) and duration of prior therapy (in months); for all other subgroups,

categorical variables were used. The analyses were conducted using SAS

version 9 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3.

Results

3.1.

Patients

The analyses included 410 and 411 patients randomized to

nivolumab and everolimus, respectively, between October

2012 and March 2014 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The

distribution of patients in each subgroup was balanced

between nivolumab and everolimus

( Table 1). The mini-

mum follow-up was 14 mo. The median follow-up among

the 227 nivolumab-randomized and 196 everolimus-ran-

domized patients who had not died at data cutoff was

22 mo (interquartile range [IQR] 20–25) and 22 mo (IQR

20–25). At data cutoff (June 2015), 67 of 406 nivolumab-

treated and 28 of 397 everolimus-treated patients contin-

ued to receive treatment. The number who continued to

receive treatment in each subgroup is shown in Supple-

mentary Fig. 1. Consistent with the overall population, the

primary reason for discontinuation in all subgroups was

disease progression.

The baseline disease characteristics of patients by

subgroups were generally similar between nivolumab

and everolimus (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2.

OS by prognostic risk group

In an assessment of OS by favorable, intermediate, and poor

MSKCC risk groups, median OS was longer in both arms in

patients with better MSKCC scores

( Fig. 1A,

Fig. 2A–C).

Among patients with poor risk who received nivolumab,

median OS was almost double compared

[4_TD$DIFF]

with everolimus

(hazard ratio 0.48;

Fig. 1A,

Fig. 2C). Results for OS by IMDC

risk group were consistent with those for MSKCC risk group

(Supplementary Fig. 2A–C;

Fig. 1A). The mortality rate at

12 mo for all subgroups was lower with nivolumab

compared

[4_TD$DIFF]

with everolimus and was particularly striking

in the poor MSKCC risk group

( Fig. 1 A).

3.3.

OS by age group

Median OS in patients aged

<

65 yr was 26.7 mo (95% CI

21.8–NR) with nivolumab and 19.9 mo (95% CI 17.4–NR)

with everolimus. Median OS in patients aged 65 yr was

23.6mo (95% CI 18.2–NR) with nivolumab and 18.5mo (95%

CI 16.4–21.6) with everolimus.

3.4.

OS by number and site of metastases

Median OS in patients with one site of metastasis was NR

with nivolumab and 29.0 mo (95% CI NR) with everolimus

(Supplementary Fig. 3A, Fig. 1A). In patients with at least

two sites of metastases, median OS was 22.2 mo (95% CI

19.1–26.7) with nivolumab and 17.6 mo (95% CI 15.6–19.8)

with everolimus (Supplementary Fig. 3B, Fig. 1A).

Median OS in patients with bone metastases was

18.5 mo (95% CI 10.2–NR) with nivolumab and 13.8 mo

(95% CI 7.0–16.4) with everolimus (Supplementary Fig. 4A,

Fig. 1A). Median OS in patients with liver metastases was

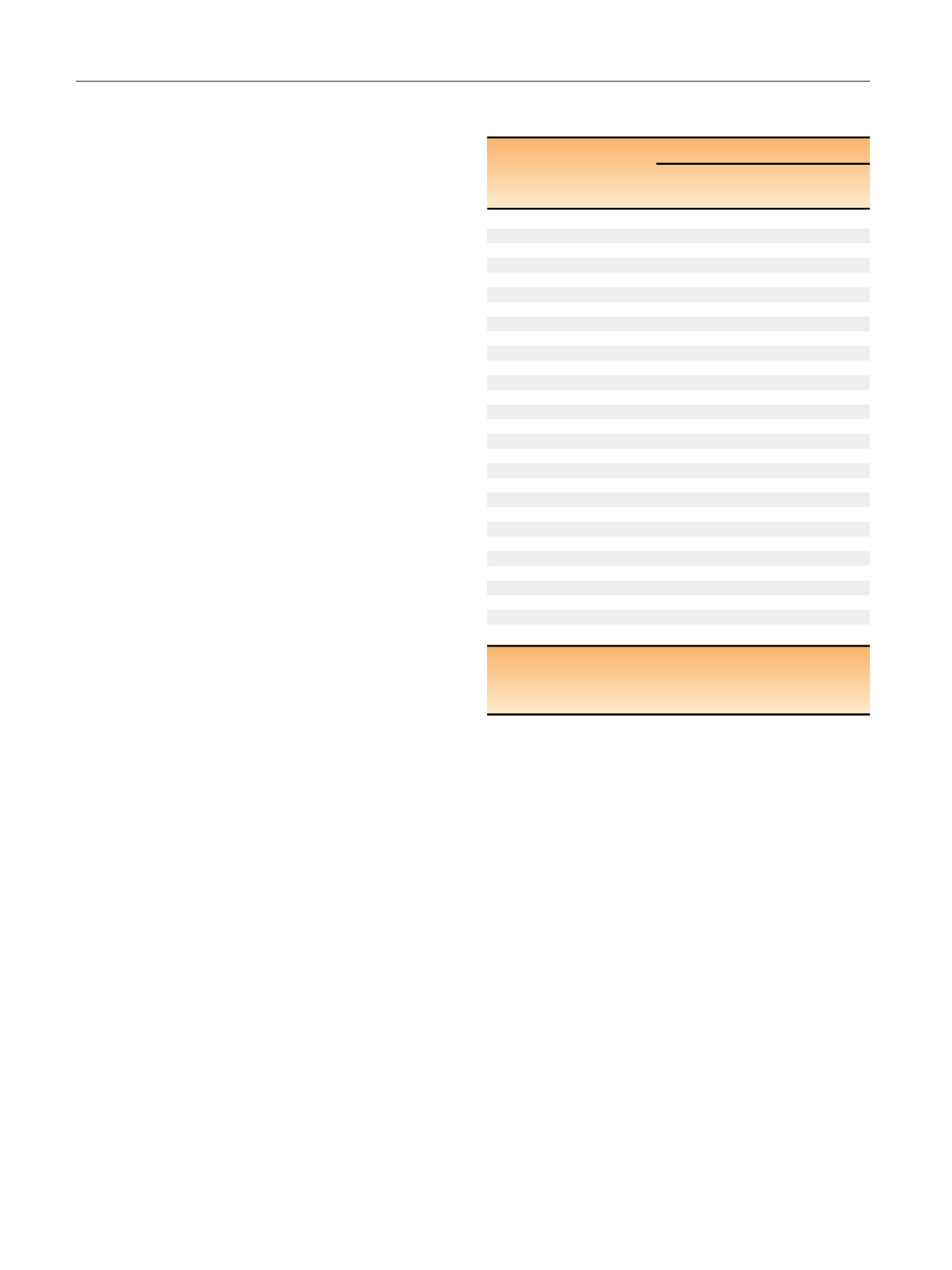

Table 1 – Distribution of randomized patients within each

subgroup

Subgroup

aPatients,

n

(%)

Nivolumab

Everolimus

(

N

= 410)

(

N

= 411)

MSKCC risk score

Favorable

137 (33)

145 (35)

Intermediate

193 (47)

192 (47)

Poor

79 (19)

74 (18)

IMDC risk score

Favorable

55 (13)

70 (17)

Intermediate

242 (59)

241 (59)

Poor

96 (23)

83 (20)

Not reported

17 (4)

17 (4)

Age group

<

65 yr

257 (63)

240 (58)

65 yr

153 (37)

171 (42)

Number of sites of metastases

1

68 (17)

71 (17)

2

341 (83)

338 (82)

Site of metastases

Bone

76 (19)

70 (17)

Liver

100 (24)

87 (21)

Lung

278 (68)

273 (66)

Prior therapy

bSunitinib

257 (63)

261 (64)

Pazopanib

126 (31)

136 (33)

Interleukin-2

42 (10)

37 (9)

Time on first-line therapy

<

6 mo

110 (27)

130 (32)

6 mo

300 (73)

281 (68)

Prior antiangiogenic therapies

1

317 (77)

312 (76)

2

90 (22)

99 (24)

IMDC = International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database

Consortium; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

a

Analysis based on case report form data.

b

Patients may have received more than one prior therapy.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 9 6 2 – 9 7 1

964