1.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death

among US men

[1] ;there are approximately 3.3 million

prostate cancer survivors, accounting for 21% of all cancer

survivors

[2].

Higher physical activity (PA) after diagnosis has consis-

tently been associated with a lower risk of dying from breast

cancer and colorectal cancer

[3–12] .Four large prospective

cohort studies suggest that postdiagnosis PA is also associated

with a lower risk of prostate cancer progression or prostate

cancer–specific mortality (PCSM)

[13–16]. However, the

strength of the evidence for PCSM is considered limited

due to concerns about reverse causation and limited power in

some of these studies

[15,16] .Therefore, a larger cohort study

with a design that minimizes bias from reverse causation is

needed. In addition, physical inactivity prior to diagnosis may

play a role in the development of tumor aggressiveness

[17] ,but this has not been well studied in relation to PCSM.

The goal of this study was to examine the associations of

pre- and postdiagnosis recreational PA with PCSM overall,

and by tumor risk category. The Cancer Prevention Study

(CPS)-II Nutrition Cohort is well suited for investigating

these associations, given its large sample size, long-term

follow-up, and detailed information on PA and important

covariates measured before and after diagnosis.

2.

Patients and methods

2.1.

Participants

Participants were drawn from the 86 402 men enrolled in the CPS-II

Nutrition Cohort, a prospective study of cancer incidence and mortality,

established by the American Cancer Society in 1992 as described in detail

elsewhere

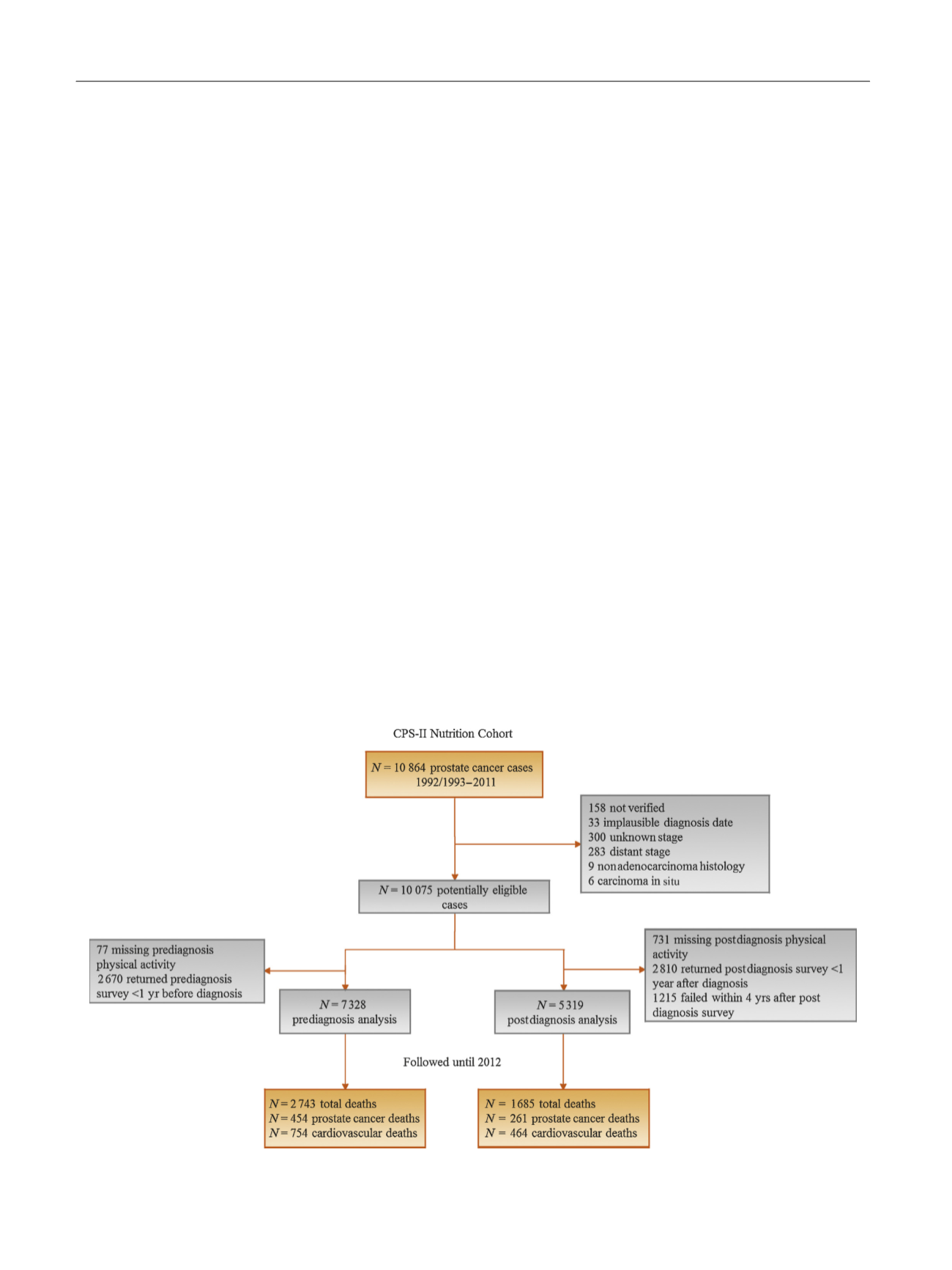

[18] .We identified 10 864 men diagnosed with prostate

cancer between 1992/1993 and June 30, 2011. After all exclusions

( Fig. 1 ), 7328 and 5319 men were included in pre- and postdiagnosis

analyses, respectively.

2.2.

Assessment of recreational PA

The amount of recreational PA per week during the past year was self-

reported on the baseline questionnaire and on biennial follow-up

questionnaires beginning in 1999 (except on the 2003 questionnaire;

available online:

https://www.cancer.org/research/we-conduct-cancer- research/epidemiology/cancer-prevention-questionnaires.html ). A meta-

bolic equivalent of task (MET) was assigned to each of the seven activities

as follows: 3.5 for walking, 3.5 for dancing, 4.0 for bicycling, 4.5 for aerobics,

6.0 for tennis or racquetball, 7.0 for jogging/running, and 7.0 for lap

swimming

[19]. Expert panels from organizations including the American

Cancer Society and American College of Sports Medicine recommend that

cancer survivors engage in a minimum of 150 min of moderate-intensity or

75 min of vigorous- intensity activity per week, or an equivalent

combination

[20,21]. Although strength training also is recommended for

cancer survivors, it was not asked on every questionnaire; thus, we focused

on aerobic exercise. We categorized the total recreational MET hours per

week (MET-h/wk) into four groups:

<

3.5, 3.5

<

8.75 (reference group),

8.75

<

17.5, and 17.5.Category 3.5

<

8.75 represents engaging in some

recreationalPA,equivalentto1–

<

2.5 hofwalkingperweek,butnotmeeting

the minimum recommendation. This reference group was selected because

it is larger than the lowest category, whichmeans that the risk estimates are

more stablewith narrower 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and is less subject

to reverse causation bias because men in the bottom category may have

reduced their activity due to illness.

Prediagnosis PA was obtained from the last questionnaire completed

at least 1 yr (median 3 yr) before prostate cancer diagnosis.

Postdiagnosis PA was obtained from the first questionnaire completed

at least 1 yr (median 3 yr) after diagnosis.

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1 – Prostate cancer cases drawn from the CPS-II Nutrition Cohort 1992/1993–2011, and number of deaths identified up to 2012. CPS = Cancer

Prevention Study.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 9 3 1 – 9 3 9

932