but not those with high-risk tumors (

p

[9_TD$DIFF]

interaction =

[10_TD$DIFF]

0.02).

A similar result was observed for walking; among men

with lower-risk tumors, those who walked for 7 h/wk

had a 47% lower risk of PCSM compared with those who

walked for 1–3 h/wk (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.33–0.86,

p

trend = 0.04).

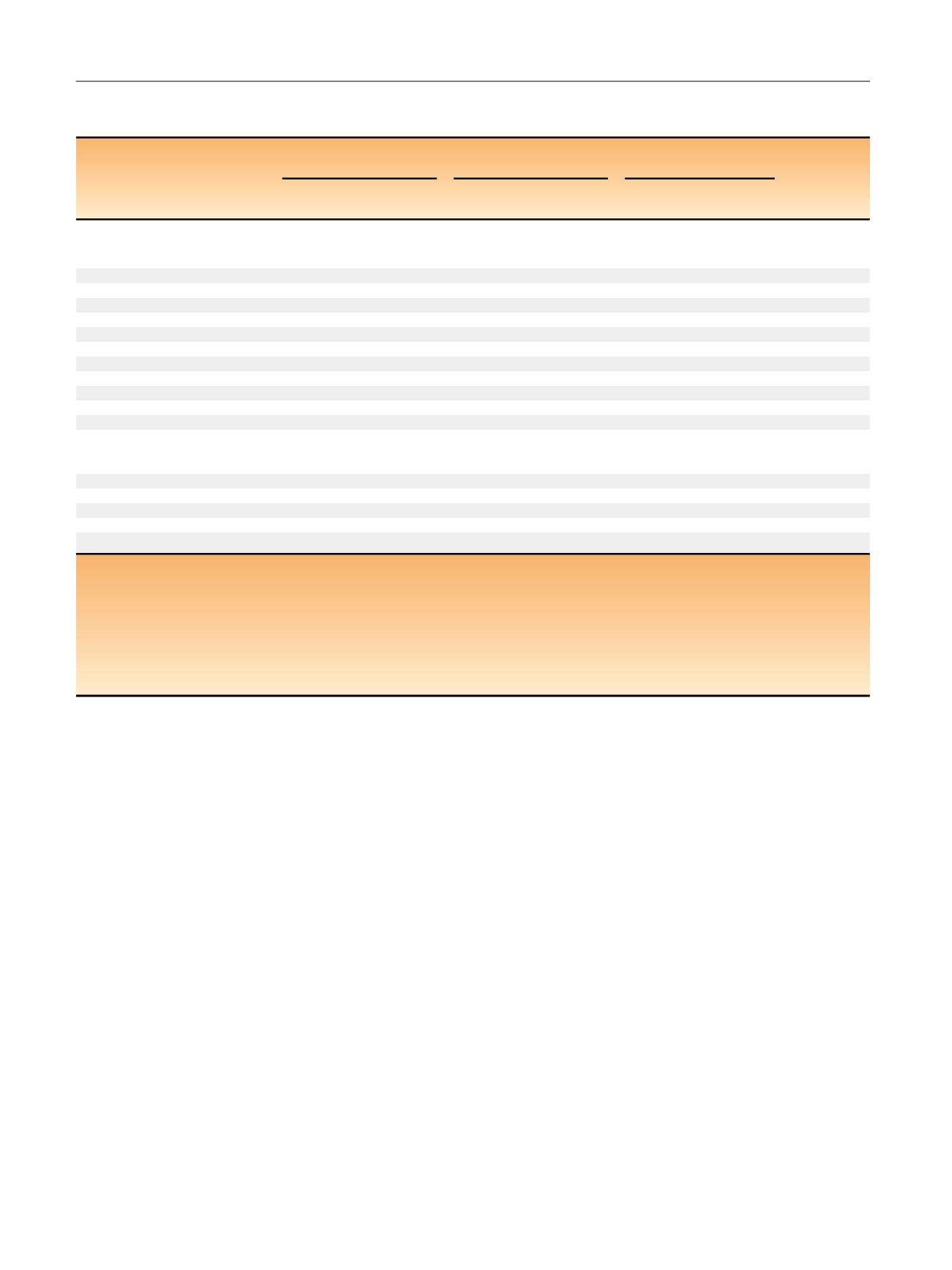

For postdiagnosis recreational PA

( Table 4), there was a

significantly lower risk of PCSM for men engaging in 17.5

MET-h/wk of recreational PA compared with those engag-

ing in 3.5–

<

8.75 MET-h/wk (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.49–0.95,

p

trend = 0.006). Further adjustment for prediagnosis METs

did not change the results (not shown). Postdiagnosis

walking, but not other recreational PA, was inversely

associated with PCSM, although the HRs were not statisti-

cally significant. The inverse association for recreational PA

did not differ by tumor risk category (

p

[9_TD$DIFF]

interaction =

[13_TD$DIFF]

0.1).

We also examined recreational PA in relation to CVD

mortality and all-cause mortality. Engaging in 17.5 MET-

h/wk of recreational PA before diagnosis was associated

with a 20% lower risk of CVD mortality (HR: 0.80, 95% CI:

0.67–0.96,

p

trend = 0.008; Supplementary Table 2). In

postdiagnosis analyses, the inverse trend (

p

trend = 0.01) for

recreational PA was primarily driven by men in the bottom

category who had a significantly higher risk of CVD

mortality (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.11–2.00) rather than by

those in the top category (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.69–1.14). A

similar result was seen for walking but not for other

recreational PA. For all-cause mortality, same comparison of

prediagnosis recreational PA ( 17.5 vs 3.5–

<

8.75 MET-h/

wk) was associated with 12% lower risk (HR: 0.88, 95% CI:

0.80–0.97,

p

trend

<

0.0001; Supplementary Table 3). In

postdiagnosis analyses, engaging in 17.5 MET-h/wk of

recreational PA was associated with a 14% lower risk of all-

cause mortality (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.75–0.98,

p

trend

<

0.0001). Similar results were seen for both walking and

other recreational PA.

The associations of pre- or postdiagnosis recreational PA

with PCSM did not differ by age at diagnosis (

<

70 and 70

yr), BMI (

<

25, 25–

<

30, and 30 kg/m

2

), smoking status

(never and ever), diagnosis year (1992–1998, 1999–2005,

and 2006–2011), or follow-up time (

<

10 and 10 yr for

prediagnosis analyses,

<

6 and 6 yr for postdiagnosis

analyses). Change in PA from pre- to postdiagnosis showed

no clear patterns of associations with PCSM (data not

shown).

4.

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort study of men diagnosed

with nonmetastatic prostate cancer, higher prediagnosis

Table 4 – Prostate cancer–specific mortality by postdiagnosis recreational physical activity among men diagnosed with nonmetastatic

prostate cancer in the CPS-II Nutrition Cohort (1992–2012)

Median

MET-h/wk

All prostate

cancer

a[12_TD$DIFF]

Lower-risk prostate

cancer

bHigh-risk prostate

cancer

cp

interaction

Deaths/

person-yr

HR

(95% CI)

Deaths/

person-yr

HR

(95% CI)

Deaths/

person-yr

HR

(95% CI)

Total recreational

physical activity

d[9_TD$DIFF]

(MET-h/wk)

[13_TD$DIFF]

0.1

<

3.5

0.9

45/3079

1.13 (0.77–1.66) 24/2116

1.16 (0.69–1.95) 15/489

1.25 (0.60–2.62)

3.5–

<

8.75

6.8

76/7526

1.00 (ref.)

49/5407

1.00 (ref.)

21/1204 1.00 (ref.)

8.75–

<

17.5

14

63/7462

0.81 (0.58–1.15) 29/5272

0.72 (0.44–1.15) 24/1305 0.77 (0.40–1.49)

17.5+

29.5

77/12 427 0.69 (0.49–0.95) 41/8966

0.67 (0.43–1.04) 28/2084 0.69 (0.37–1.29)

p

trend

0.006

0.04

0.1

Walking

d , e (h/wk)

0.36

<

1

0

60/4915

1.07 (0.77–1.49) 29/3346

0.92 (0.58–1.46) 23/775

1.77 (0.95–3.29)

1–3

7

106/11 679 1.00 (ref.)

68/8504

1.00 (ref.)

28/1832 1.00 (ref.)

4–6

14

52/6866

0.85 (0.60–1.20) 23/4834

0.68 (0.41–1.10) 21/1306 1.10 (0.58–2.06)

7

24.5

43/7034

0.76 (0.53–1.10) 23/5078

0.70 (0.43–1.15) 16/1169 1.01 (0.52–1.98)

p

trend

0.07

0.2

0.2

Other recreational

physical activity

d[14_TD$DIFF]

, f(MET-h/wk)

0.49

<

3.5

0

177/17 758 1.38 (0.96–1.99) 101/12 562 1.62 (0.97–2.69) 57/3 088 1.03 (0.56–1.92)

3.5–

<

8.75

5.5

38/5829

1.00 (ref.)

19/4137

1.00 (ref.)

16/917

1.00 (ref.)

8.75–

<

17.5

12.5

27/3901

1.05 (0.63–1.75) 13/2925

1.06 (0.51–2.20) 11/603

1.01 (0.42–2.41)

17.5+

28

19/3006

1.15 (0.65–2.02) 10/2137

1.23 (0.56–2.70) 4/474

0.51 (0.15–1.71)

p

trend

0.2

0.2

0.3

CPS = Cancer Prevention Study; HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; MET = metabolic equivalent task; ref. = reference.

a

Includes T1–T2 cancers with unknown Gleason score not included in lower- or high-risk categories.

b

Defined as Gleason score 2–7 and T1–T2.

c

Defined as Gleason score 8–10 or T3–T4 or nodal involvement.

d

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, race, calendar year of diagnosis, tumor extent, nodal involvement, Gleason score, education, family history of prostate cancer,

initial treatment, history of prediagnosis prostate-specific antigen testing, postdiagnosis cardiovascular disease history, postdiagnosis other cancer history,

postdiagnosis body mass index, postdiagnosis smoking status, prediagnosis red meat and processed meat intake, and postdiagnosis sitting time.

e

Further adjusted for other recreational physical activity.

f

MET hours of other physical activity is calculated as total recreational MET hours minus walking MET hours; model further adjusted for walking.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 9 3 1 – 9 3 9

936